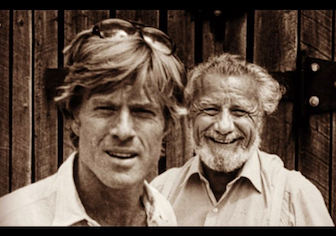

This is my final section [for now] on Frank Daniel, the Stanislavski of Screenwriting. In this last part of his farewell talk with students at Columbia, circa 1986, he touches on dreams, genre, character, Amadeus, and common sense.

He inspired many filmmakers: Terrence Malick, Paul Schrader, Jon Avnet, Martin Brest, David Lynch, Milos Forman, Jiri Menzel — and many more.

He was the first foreigner admitted to the Russian State Film School, and he became a sought-after educator: Dean of FAMU in Prague, instructor at Carleton College, Head of the American Film Institute, Screenwriting at Columbia, Artistic Director at the Sundance Institute, and Dean of USC School of Cinema-Television.

He manifested waves of creative film energy everywhere he went.

Speaking of the late Daniel in a 1996 interview, David Lynch said, “I am sorry to say he died not long ago, and I have to tell you that he was my only teacher. He gave much to other people, he helped many people. He was a noble-minded and non-egoistic man, and no one understood the art of film-making as he did. He understood it and truly loved it – his criticism was always constructive and never purposely offended anybody. He was open about saying what he didn’t like, but he did it in a way that would help you. And that cannot be said about most of the critics in USA. I am very sorry he is not here.”

{Kinorevue, July–August 1996}

THE LOST TAPES: FRANK DANIEL Q&A (pt 4)

Dreams and Nightmares

Q: What is the best way to deal with dreams and visions?

FD: Well it’s the same thing as dealing with emotions and thinking. You externalize it. For instance, dreams and visions can be used directly, as you have seen in many movies. You can demonstrate, you can perform the dreams, and if the intention and the main thrust of the story is based upon those dreams, and directly connected with them then there is no problem if they come true.

If you have a dreamer as the main character then obviously we must get into his dreams. How his dreams and his reality conflict with each other complete the story. It can be played on two levels; one is the dream, the internal stuff, and one is the reality around the character.

In 8 1/2, you have nightmares. It starts with one. Then you have a total daydream about Claudia Cardinale. The main character’s daydream is his belief that she will help him find a solution to all his problems. Then you have remembrances, of his childhood, Sarabina, school, etc. And then you have the realities, so there are four layers of story material. The state in which those different levels of dreaming are dealt with is distinct, and they are all distinguished from the reality. I don’t think Fellini was looking for some formula, he just relied upon himself and the characters and their own experience.

Real dreams and nightmares look different from our daydreams. So you just dig out the things that you know from your own experience. If they are your dreams, and if they are your demons, then they’ll look true, and everybody will understand them. How your mind operates is one of the areas that film should explore. Unfortunately there are so many clichés in the use of flashbacks and memories that it’s usually not an exploration but simple theft.

Thinking in Terms of Genre

Q: Do you classify thinking in terms of genre as part of critical thinking? That it’s not helpful, creative enough? That it’s not part of the analytical process?

FD: I don’t believe that ignorance is useful. Knowing about genres helps, one should know as much as possible, and to understand genre cannot hurt your writing. But if you start with a desire to write the genre story, you have eliminated part of your creativity, because you are actually giving up. You are putting yourself under a certain pressure.

Q: So at what point do you bring that into the process?

FD: If you get an idea for a western, because you know something that has not been told, then write it. Then, when you have written the story of yours, you can ask yourself all those questions like, did I steal it from somebody? You have to understand the basic techniques of humor if you want to write a comedy. But that doesn’t mean that you start repeating old stories, old patterns, old gags. I would like to write a screwball comedy. You ask: What do I need? A screwball character. Do I know any? When you get a screwball character, the story begins to emerge, and then the genre flows from that naturally.

Amadeus and Common Sense

Q: I’m confused about who the main character in Amadeus is. The story is about Mozart, but it’s more about Salieri.

FD: Amadeus is the main character. Salieri, the narrator in this case, helps to see the main character’s story with an additional irony, or additional insight, but you don’t identify with Salieri.

Q: To some extent you do.

FD: You identify with every character in the movie if you have scenes in which the main character is not present. At that moment it is somebody else’s scene, so you are getting into the shoes of a subsidiary character. If you have an omniscient point of view you can change your allegiance accordingly. You can be in the shoes of different characters, and if you use a subsidiary character as a narrator, or “a raisonneur,” a type of narrator, who is part of the action, and at the same time tries to figure out what the meaning of the main story is, sometimes you get into his shoes. You pity the character. You can feel compassion for him. But the main story, the main identification, is with the main character. Otherwise there is no unity.

Q: There is no what?

FD: Unity. Unity of effect, which is the major objective that we are after. All these things are common sense. This is not something that people invented, or created to come up with a theory, or a prescription, or whatever. It’s just common sense. What do you want the audience to feel? What should they know at this moment? What should be hidden from them? When should you reveal? Those are very simple questions. It’s a part of the craft. That’s why it’s not really mysterious. You can always find out, if you look at a script carefully, why it doesn’t work, and what’s wrong. A film is just a presentation, in action, of a story to create an emotional impact on the audience. So the characters must be in action. You cannot have characters just talking, because then you change the audience into listeners instead of viewers, and motion pictures were created because of the motion. That’s how movies differ from still photography, why Lumiere and Edison invented it. Action is the only tool that you have for painting characters. And action doesn’t mean only physical action. Action is a purposeful drive of the character towards an objective. It includes thinking. It includes feeling. It includes planning, remembering, doubting, hesitating, talking, asking, lying, dancing, singing, crying, laughing, whatever. Okay?

Good Luck!

Thank you, Frank Daniel, for sharing your knowledge, wisdom and experience. I wish I could have been your student, but you will forever be my teacher-in-absentia and an inspiration.

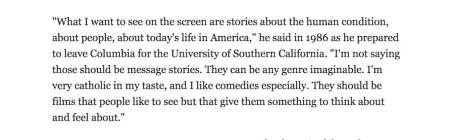

A quote from Frank Daniel’s obituary in the New York Times, 1996:

Tags: AFI, artistic director, character, Cinema, Columbia University, common sense, David Lynch, dreams, FAMU, film education, Film School, film student, genre, Gerasimov, Jiri Menzel, Jon Avnet, mentor, Milos Forman, Paul Schrader, School of Cinema, screenwriting, scriptwriting, Sundance, Terrence Malick, USC

Leave a comment